FILM THEORY & CRITICISM

Pedro Almodovar's Renegotiation of the Spanish Identity

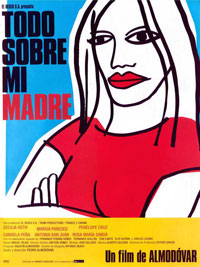

Spanish cinema has been indelibly marked by the contribution of the films of Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóvar. The name has become synonymous with Spanish cinema, and his filmic influence has marked the reformation of post-Franco Spain. Almodóvar's films are ripe with reference to the Spanish identity and what the "new Spain" looks like in a post-Franco society. Almodóvar's films reappropriate "Spanishness" in terms of the family, sexuality, religion, gender, and pleasure. He meticulously crafts a world that is held together with its own rules of generic hybridity, where the marginalized become the center, gender is nothing more than a social construct, traditional Spanish icons are renegotiated with new meanings, and the pursuit of pleasure and desire is at the forefront of an amoral, yet authentic Spanish identity.

In recognizing how Almodóvar reappropriates Spanish identity, it is important to understand the context of the Spain from which he emerged. Under Franco rule, censorship and repression were the mode, and expectations of morality and structure were widespread and heavily expected from Spanish citizens. It was a heavily patriarchal society, yet the father figure was distant and absent. Almodóvar expresses this idea quite frequently in his films by featuring mostly women, and exalting the mother. The father figure is markedly and unapologetically absent.

In recognizing how Almodóvar reappropriates Spanish identity, it is important to understand the context of the Spain from which he emerged. Under Franco rule, censorship and repression were the mode, and expectations of morality and structure were widespread and heavily expected from Spanish citizens. It was a heavily patriarchal society, yet the father figure was distant and absent. Almodóvar expresses this idea quite frequently in his films by featuring mostly women, and exalting the mother. The father figure is markedly and unapologetically absent.

Under Franco, urban areas and cities were demonized in favor of the more domesticated country life. Marvin D'Lugo points out "Francoism constructed its own ideal of the Spanish nation against the models of social and political deviance embodied as much by the urban life styles of Madrid and Barcelona as by the external otherness of foreign political ideologies and social customs" (D'Lugo 47). It is no coincidence, that Almodóvar chooses these cities as the locale for the majority of his films. The city, for Almodóvar represents a new, post-Franco Spain. There is a restructuring of society's values, and the city is its mise-en-scene. D'Lugo continues "This foregrounding of the city as an assertion of a vibrant Spanish cultural identity is built around a rejection of the traditions that ordered Spanish social life for four decades" (D'Lugo 47). Madrid and Barcelona are characters in the landscape of a new Spanish identity. Almodóvar pays homage to the city in his films often with beautiful long shots of cityscapes. In All About My Mother (1998), Manuela's (Cecila Roth) arrival to Barcelona is a poetic gesture to the city with shots overlooking its entire breadth and expanse as well as a shot-reverse-shot between Manuela and a cathedral designed by famed architect Antonio Gaudi, as though the city were a safe haven, or a place of rebirth for Manuela. In this quick, yet important interchange, Almodóvar reconciles a return to the city as a sort of spiritual experience. In direct opposition to Franco the city is celebrated as a place free from the repression and censorship of a dictatorial society.

Almodóvar creates his own version of what post-Franco Spain looks like and who inhabits it. He comments on this very fact, stating that the characters in his film "...represent more than others, I suppose, the new Spain, this kind of new mentality that appears in Spain after Franco dies...I think in my films they see how Spain has changed, above all, because now it is possible to do this kind of film here" (Kinder 36). There is an a self-awareness that he is representing the new Spain and asserting its identity, which becomes an important marker in his body of work.

The oeuvre of Almodóvar is marked by melodrama, but at the same time he has created its own set of rules that defy placement in a particular genre. It is difficult to assign a single generic association because he has infused into each film a delicate blending of styles and modes that are held together by their own unique set of constructs. Ernesto Acevedo-Munoz asserts that each film "...seem to be stories in search of a format, always about to spin out of control but finally held together by their own unstable generic and formal rules. The search itself for a satisfactory formal identity and the films' dependency on intertexuality, camp appropriations of Spanishness,' and generic instability are among their defining characteristics" (Acevedo-Munoz 25). This hybridization is a metaphor for the Spanish identity and is one of the ways that Almodóvar is able to assert the "new Spain."

The oeuvre of Almodóvar is marked by melodrama, but at the same time he has created its own set of rules that defy placement in a particular genre. It is difficult to assign a single generic association because he has infused into each film a delicate blending of styles and modes that are held together by their own unique set of constructs. Ernesto Acevedo-Munoz asserts that each film "...seem to be stories in search of a format, always about to spin out of control but finally held together by their own unstable generic and formal rules. The search itself for a satisfactory formal identity and the films' dependency on intertexuality, camp appropriations of Spanishness,' and generic instability are among their defining characteristics" (Acevedo-Munoz 25). This hybridization is a metaphor for the Spanish identity and is one of the ways that Almodóvar is able to assert the "new Spain."

A fundamental aspect in all of Almodóvar's films is an emphasis on intertexuality not just with other textual sources, but with his other films particular to his body of work as well. This intertexuality emphasizes an awareness and self-reflexivity that is effective in making its point, but not abrasive in alienating the viewer.

This type of intertexuality is most effectively seen in All About My Mother. The film's plot relies heavily on the integration of the film All About Eve (1950), from which the movie's title is drawn, and Tennessee Williams' play A Streetcar Named Desire. Both texts serve as a locus for the characters throughout the film. It is within the scope of these texts that the characters negotiate their identities through performance. Almodóvar uses it as a forum to comment upon the authenticity of identity, and explore what is authentic. This can be seen when Manuela takes on the role of Stella in the performance for Nina (Candela Pena) who is too strung out to perform. Not only does the situation hearken to the story line of All About Eve, but also, Manuela experiences authentic emotion as she is playing the role of Stella. The primal scream that she releases as her character goes into labor is real emotion for Manuela, and not merely a conjured performance. While on stage, she is transported back to where she met "Lola" or Esteban Sr. (Toni Canto), and at the same time feels again the birth pains of carrying her own son who has recently died. Almodóvar juxtaposes performance and the authentic amidst a web of intertextual references. He asserts that what is real, is what is felt. In fact, earlier in the film, the highly likeable transvestite Agrado (Antonia San Juan) insightfully states: "All I have that's real are my feelings..." For Almodóvar what is felt is where the authentic self is negotiated, and drawing that out of the various textual references is an important commentary on acting and performance itself.

Another element of Almodóvar's intertexuality is the fluidity and commentary that is created within his own film cannon. His films reference one another, and are self-contained sources of intertexuality. For example, The Flower of My Secret (1995) begins with a sequence where a character named Manuela is shooting a training video for a hospital to train and instruct nurses on how to counsel families with brain dead relatives into organ donation. This same sequence, almost shot for shot is used in All About My Mother, even utilizing the same character of Manuela. Also in The Flower of My Secret, a story that Leo (Marisa Paredes) writes about a girl who kills her father after he tries to rape her, and then hides the body in a restaurant freezer is the basis for the plot of his film Volver (2006). Again, the character of Rosa (Penelope Cruz) in All About My Mother seems to be a continuation of the renegade nun also named Rosa in Dark Habits (1983). The utilization of this self-reflexivity within his own work reinforces his renegotiation of the Spanish identity. He creates a world within his films that are the representation of a post-Franco Spain, and continues to explore and build upon the identity that he asserts within the characters that he creates.

Another element of Almodóvar's intertexuality is the fluidity and commentary that is created within his own film cannon. His films reference one another, and are self-contained sources of intertexuality. For example, The Flower of My Secret (1995) begins with a sequence where a character named Manuela is shooting a training video for a hospital to train and instruct nurses on how to counsel families with brain dead relatives into organ donation. This same sequence, almost shot for shot is used in All About My Mother, even utilizing the same character of Manuela. Also in The Flower of My Secret, a story that Leo (Marisa Paredes) writes about a girl who kills her father after he tries to rape her, and then hides the body in a restaurant freezer is the basis for the plot of his film Volver (2006). Again, the character of Rosa (Penelope Cruz) in All About My Mother seems to be a continuation of the renegade nun also named Rosa in Dark Habits (1983). The utilization of this self-reflexivity within his own work reinforces his renegotiation of the Spanish identity. He creates a world within his films that are the representation of a post-Franco Spain, and continues to explore and build upon the identity that he asserts within the characters that he creates.

Almodóvar does this again in two of his more recent films. The last shot in All About My Mother shows a closed curtain on a stage. Almodóvar's subsequent film Talk to Her (2002) opens with the exact same curtain. It's as though he is picking up exactly where he left off. Additionally, there are a couple of identical shots that the film shares in regards to the stage. In both films, the viewer sees shots of the characters watching a stage performance. In All About My Mother it is the performance of A Streetcar Named Desire, and in Talk to Her, it is a beautiful ballet choreographed by Pina Bausch. These mirroring scenes call to mind not only the self-reflexive aspect of the voyeurism of cinema, but also Almodóvar's own film intertexuality. While complicated plot elements and heavy reliance on the melodramatic form shape many of his films, they are filled out by other complex elements such as the aforementioned intertexuality. This generic hybridity, in which Almodóvar keeps his films from spinning out of control by relying on his own internal set of generic rules is a key element to his oeuvre.

Part of Almodóvar's unique "formula" is the fact that his films seem to contain no moral judgments within its confines. Each film is allowed to express itself based on the characters' pursuit of hedonistic instincts. He deliberately focuses on characters that are not part of the centrally accepted society. He celebrates those who are traditionally marginalized. Although the characters are the "dregs" of society, so to speak, he is able to circumvent the marginalization of his own films. Marsha Kinder illuminates:

Part of Almodóvar's unique "formula" is the fact that his films seem to contain no moral judgments within its confines. Each film is allowed to express itself based on the characters' pursuit of hedonistic instincts. He deliberately focuses on characters that are not part of the centrally accepted society. He celebrates those who are traditionally marginalized. Although the characters are the "dregs" of society, so to speak, he is able to circumvent the marginalization of his own films. Marsha Kinder illuminates:

Almodóvar's films have a curious way of resisting marginalization. Never limiting himself to a single protagonist, he chooses an ensemble of homosexual, bisexual, transsexual, doper, punk, terrorist characters who refuse to be ghettoized into diverse subcultures because they are figured as part of the new Spanish mentality'?a fast-paced revolt that relentlessly pursues pleasure rather than power, and a postmodern erasure of all repressive boundaries and taboos associated with Spain's medieval, fascist, and modernist heritage (Kinder 34).

It is common practice for Almodóvar to bring to the forefront those that Hollywood, and more importantly Franco Spain deemed the repressed other. Not only do these characters take center stage over the traditional protagonist, but also, they inhabit a world that is essentially apolitical and amoral. In other words, there is nothing uncommon about a transvestite, prostitute, homosexual, etc. being the focal point for the audience. Almodóvar asserts no value judgments within his filmic work, in fact, he observes, "It's very dangerous to see my films with conventionally morality. I have my own morality. And so do my films" (Kinder 42). In this way, by making these characters and situations central, Ernesto Acevedo-Munoz comments, Almodóvar "unmasks the manufactured centralized national identity seen in Francoist cinema while proposing a revision of Spain's cultural identity in the recent past" (Acevedo-Munoz 26). He is able to reappropriate the repressed and disassociated, creating a forum for a new Spanish identity to emerge where these "types" people have a voice.

To Almodóvar, this is the "new Spain;" a society that embraces the pursuit of desire above all, and the reconciliation of the other. In fact, the concept of the other is highly absent within his films because the other is made to be the identifier for the audience. The highly sexualized behavior, unapologetic hedonism, normalization of alternative gender identities and lifestyles, are all typically categorized as "social transgressions," yet as Jose Arroyo determines, "...these social transgressions are narrated as perfectly moral within the films' terms, and audiences are asked to identify with the transgressor" (Hill and Gibson 108). In traditional cinematic terms, asking the audience to identify with "the other" is not easy to pull off, but Almodóvar is able to create non-traditional characters that are likeable, identifiable, and most importantly, unrepentant for their self-expression. This is the post-Franco Spain that Almodóvar presents. He embraces all that was repressed under the regime, and not only embraces it, but also renegotiates the Spanish identity within the terms of an amoral acceptance of the marginalized.

A paramount theme in this same vein is the recognition of how gender is socially constructed, and the way in which Almodóvar subsequently deconstructs those roles. Gender is a point of fluidity rather than certainty. Transvestites, homosexuals, and bisexual characters feature prominently in many of his films. In this way, Almodóvar captures the notion that gender and sexuality are not rigid forms, but part of the new Spanish identity that represents a high degree of mutability and variance. The "breaking down" of gender roles is part of Almodóvar's reappropriation of the identity. Ernesto Acevedo-Munoz points out "Generic definition' has come with a volatile gender un-definition of key characters whose transitional identities are paradoxically symbolic of their stability and not of crisis" (Acevedo-Munoz 26). The transition is just as important in the discovery of the post-Franco identity as the eventual reconciliation. It is a paradoxical idea, that the instability is a signifier of stability and not of crisis, but it is a way that Almodóvar is able to appropriate meaning and authenticity on his own terms, fracturing any marker of Francoist Spain.

Possibly the best example of this idea is the transvestite who features prominently in several of Almodóvar's films. Alejandro Yarza states that "transvestite is the indicator of a crisis of the conventional sexual and cinematic taxonomic systems,' a monster' that, along with Almodóvar's generic cross-references, exemplifies the nation's cultural anxiety'" (Acevedo-Munoz 26). The transvestite is both male and female, demonstrating again the fluidity of gender, while at the same time; the transvestite is where the new Spanish identity is reconciled. In All About My Mother Agrado is seen as one of the most authentic characters in the film. Although she is filled with pints of silicone and her body is far removed from its "natural" state, she is authentic, because she is "who she has dreamed of being." There is an acceptance of the absurd within Agrado. Her discourse about her body on stage takes place behind a closed curtain. Here, Almodóvar reinforces the authentic nature of her identity because the stage curtain is closed; this is not a performance, but rather an expression of the authentic. Ernesto Acevedo-Munoz continues that it is "...representative of the process of reconciliation and of the settling of identity issues, since other critics have argued that transvestism and transsexuality have been seen as a sign of the nations anxiety' in Almodóvar's films" (Acevedo-Munoz 30). Agrado represents both the anxiety over, and the reconciliation of the Spanish identity. In Agrado, there is a "coming to terms" with the breakdown of tradition and an embracing of the post-Franco alternative that Almodóvar asserts.

Part of the irony of Almodóvar's films are the fact that traditional Spanish icons are plentiful, but their meanings are reassigned and reinterpreted to identify with a post-Franco Spain. Almodóvar reappropriates icons of religion, sexuality, the family model, and tradition in order to reconfigure how "Spanishness" is appropriated. Religion is claimed by the director and reconstituted to serve the needs of the characters, rather than a source of oppression for the people. His films display altars filled with kitsch icons such as pictures of Marilyn Monroe and various items of camp. In the film Dark Habits Almodóvar completely renegotiates the terms of religion with a plot based on a convent of nuns who deal marijuana, read sensationalist literature, and exploit one another with the use of self-flagellating names such as "rat." The convent also keeps a pet tiger, drawing in elements of the surreal and absurd, with which Almodóvar is able to comment on the context of religion itself. He removes from religion the overbearing, suffocating qualities, and attributes to it an absurdity and playfulness that reconciles a revised version of God that serves the characters, rather than the characters serving God.

Part of the irony of Almodóvar's films are the fact that traditional Spanish icons are plentiful, but their meanings are reassigned and reinterpreted to identify with a post-Franco Spain. Almodóvar reappropriates icons of religion, sexuality, the family model, and tradition in order to reconfigure how "Spanishness" is appropriated. Religion is claimed by the director and reconstituted to serve the needs of the characters, rather than a source of oppression for the people. His films display altars filled with kitsch icons such as pictures of Marilyn Monroe and various items of camp. In the film Dark Habits Almodóvar completely renegotiates the terms of religion with a plot based on a convent of nuns who deal marijuana, read sensationalist literature, and exploit one another with the use of self-flagellating names such as "rat." The convent also keeps a pet tiger, drawing in elements of the surreal and absurd, with which Almodóvar is able to comment on the context of religion itself. He removes from religion the overbearing, suffocating qualities, and attributes to it an absurdity and playfulness that reconciles a revised version of God that serves the characters, rather than the characters serving God.

In a similar way, icons of Spanish tradition are constant sources of renegotiation. The idea of the Matador is reconstituted in the film Talk to Her where Lydia (Rosario Flores) fulfills the role of a bullfighter. In a traditionally male role, Lydia is the embodiment of Almodóvar's gender transfiguration and the usurping of traditional Spanish values. Lydia embraces both the masculine and the feminine, which imbues the classic Spanish icon with a new, altered identity.

Another aspect that Almodóvar undertakes is the restructuring of the traditional Spanish family model. Almodóvar removes almost entirely the father figure from the equation, and in doing so, Ernesto Acevedo-Munoz articulates, that Almodóvar is "...violating the overwhelming, powerful, all-knowing and yet benevolent Father figure for decades celebrated in Spanish cinema" (Acevedo-Munoz 26). Instead, the father figures are removed, or their identities are completely renegotiated to fit within the schema of Almodóvar's appropriation of familial logistics. Take for example, the father figure that is seen in All About My Mother. Lola is portrayed as the deserted, distant father from Esteban Jr. and Manuela, but he is also a transvestite, which in the discourse of Almodóvar's aesthetic is traditionally representative of the anxiety and displacement over the identity. By the end of the film, there is reconciliation with Lola, suggesting a new image for the father figure, and what the father figure represents in a post-Franco society. This occurrence is arguably found only in Almodóvar's later films, as his assertions concerning the new Spanish identity have matured, and the father figure can be reappropriated and accepted as part of the new Spanish identity, but only on Almodóvar's terms.

A common thread that ties the majority of Almodóvar's films together is his characters' pursuit of desire. He emphasizes in this way a de-emphasis on the imposed morality of Franco's Spain, and establishes a new identity that embraces the accrual of hedonistic pleasures. Almodóvar presents a complete disassociation with the old regime's way of thinking and way of life. He states:

We have lost the fear of the earthly power (the police), and of celestial power (the Church)... And we have recuperated the inclination toward sensuality, something typically Mediterranean. We have become more skeptical, without losing the joy of living. We don't have confidence in the future, but we are constructing a past for ourselves because we don't like the one we have (D'Lugo 65).

This is precisely what he does in his films: all ties with the past are broken in favor of a return to what he believes is a more authentic form of the Spanish identity; a more sexual, self-gratifying identity, that refuses to indulge in any sort of moral value judgments.

This more authentic identity is appropriated within the scope of Almodóvar's films, as he allows his characters to not only live self-indulgently, but also to be a byproduct of their own behaviors. In Talk to Her, the character of Benigno (Javier Camara) is likeable, but a little disturbing at the same time. His pursuit of Alicia, which is the locus of his desire, borders on sociopathic, as he eventually follows that desire to raping the unconscious Alicia. While the behavior may be detestable, the audience still responds and identifies with Benigno. This is one of Almodóvar's strengths: he negotiates Spanish identity, embraces all pursuit of desire, but also does not omit consequences from his films. At the same time, Almodóvar creates a sympathy and identification with the characters no matter their faults.

This more authentic identity is appropriated within the scope of Almodóvar's films, as he allows his characters to not only live self-indulgently, but also to be a byproduct of their own behaviors. In Talk to Her, the character of Benigno (Javier Camara) is likeable, but a little disturbing at the same time. His pursuit of Alicia, which is the locus of his desire, borders on sociopathic, as he eventually follows that desire to raping the unconscious Alicia. While the behavior may be detestable, the audience still responds and identifies with Benigno. This is one of Almodóvar's strengths: he negotiates Spanish identity, embraces all pursuit of desire, but also does not omit consequences from his films. At the same time, Almodóvar creates a sympathy and identification with the characters no matter their faults.

The films of Almodóvar have been canonized as classics of world cinema. In the words of Jose Arroyo, "Almodóvar's films are urban, camp, frivolous, sexy, colorful, fun, and free. They epitomize how post-Franco Spain liked to see itself and how it liked to be seen" (Hill and Gibson 108). His films go beyond the frivolity however, and elicit complex and varied emotions that define ultimately define his aesthetic. Almodóvar has renegotiated what it means to be Spanish and reappropriated its ideals. The authentic identity for Almodóvar is one free from the confines of strict morality, and one instead that embraces the things and people that are just off-centre, much like Almodóvar himself.

Works Cited:

- Acevedo-Munoz, Ernesto R. "The Body and Spain: Pedro Almodóvar's All About My Mother." Quarterly Review of Film and Video Vol. 21 (2004): 25-38.

- D'Lugo, Marvin. "Almodóvar's City of Desire." Quarterly Review of Film and Video Vol. 13, No. 4 ( 1991): 47-65.

- Hill, John, Gibson, Pamela Church. World Cinema: Critical Approaches. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Kinder, Marsha. "Pleasure and the New Spanish Mentality: A Conversation with Pedro Almodóvar." Film Quarterly Vol. 41, No. 1 (1987): 33-44.

- Kinder, Marsha. "Reinventing the Motherland: Almodóvar's Brain-Dead Trilogy." Film Quarterly Vol. 58, No. 2 (2004) 9-25.

One Comment

By Paul on November 4, 2011 at 1:07 PM

Hello

Just read your piece above and learned more from you in these pages than I gleaned from my entire course on Almodovar here in NYC. you have a gift. You should keep writing.

the best of luck.

Leave a Comment