FILM THEORY & CRITICISM

Futurism: Art's Reaction to the Cinema

Very rarely does the world of art and film intersect. Obviously movies draw inspiration from the classic paintings of Art History (for example, Terrence Malick's Days of Heaven draws heavily from the visual style of the paintings of Andrew Wyeth.) Yet, never have these two mediums built off of one another, or responded to each other. However, there was one same moment in the history of art where an entire movement was created as a reaction to film, and that was Futurism.

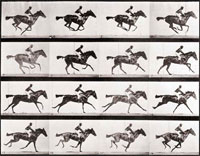

Even though Futurism occurred during the beginning of the twentieth century, its origins can be traced back to the 1800's. During the middle and end of the 19th century, the art world changed drastically due to the new invention of photography. Artists were no longer needed to depict reality since science ushered a new medium of capturing the real world in a single frame. However, photography accidentally ushered in a new art form that would change not only how people captured reality, but also how audiences viewed entertainment: that invention was the cinema. In 1872, photographer Eadweard Muybridge was hired by Leland Stanford to photograph a horse running to see if its hooves came entirely off the ground during a gallop. The experiment (Figure 1) not only discovered that a horse at one point has all of its hooves off the ground as it runs, but also that by putting a series of images together, the illusion of motion can be created. Now that photography was not only able to depict reality, but also movement, art was no longer required to paint only realistic figures and objects. But during the beginning of the 20th century, when the cinema was gaining popularity every passing day, an art movement emerged that would challenge the visual aesthetic of movies, thus came the rise of Futurism. Because Futurism is able to depict movement in a single frame, as opposed to cinema's miles and miles of footage, Futurism was able to challenge the new form of entertainment not only aesthetically, but also thematically.

Even though Futurism occurred during the beginning of the twentieth century, its origins can be traced back to the 1800's. During the middle and end of the 19th century, the art world changed drastically due to the new invention of photography. Artists were no longer needed to depict reality since science ushered a new medium of capturing the real world in a single frame. However, photography accidentally ushered in a new art form that would change not only how people captured reality, but also how audiences viewed entertainment: that invention was the cinema. In 1872, photographer Eadweard Muybridge was hired by Leland Stanford to photograph a horse running to see if its hooves came entirely off the ground during a gallop. The experiment (Figure 1) not only discovered that a horse at one point has all of its hooves off the ground as it runs, but also that by putting a series of images together, the illusion of motion can be created. Now that photography was not only able to depict reality, but also movement, art was no longer required to paint only realistic figures and objects. But during the beginning of the 20th century, when the cinema was gaining popularity every passing day, an art movement emerged that would challenge the visual aesthetic of movies, thus came the rise of Futurism. Because Futurism is able to depict movement in a single frame, as opposed to cinema's miles and miles of footage, Futurism was able to challenge the new form of entertainment not only aesthetically, but also thematically.

When Muybridge presented the results of his experiment to an audience, he invented a device called a zoopraxiscope to project the images sequentially on a screen. It was so realistic that one viewer said it "threw upon the screen apparently the living, moving animals" (Kleiner, 650). Because the results were so realistic, this new medium took the goal of Realism by furthering the progress between science and progress. It was not long until Auguste and Louis Lumiere in France, and Thomas Edison in America started exploring the narrative possibilities of cinema. The Lumiere's filmed real life events on location, and Edison filmed staged reenactments in one of the first movie studios called the Black Maria. During the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, cinema became an increasingly popular pastime, and the rise of the first movie stars like Charles Chaplin and Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle only propelled cinema further into the public eye.

When Muybridge presented the results of his experiment to an audience, he invented a device called a zoopraxiscope to project the images sequentially on a screen. It was so realistic that one viewer said it "threw upon the screen apparently the living, moving animals" (Kleiner, 650). Because the results were so realistic, this new medium took the goal of Realism by furthering the progress between science and progress. It was not long until Auguste and Louis Lumiere in France, and Thomas Edison in America started exploring the narrative possibilities of cinema. The Lumiere's filmed real life events on location, and Edison filmed staged reenactments in one of the first movie studios called the Black Maria. During the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, cinema became an increasingly popular pastime, and the rise of the first movie stars like Charles Chaplin and Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle only propelled cinema further into the public eye.

During this fruitful time for film, the radical new art called Futurism was started by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. In his manifesto, Marinetti described Futurism as "the exaltation of speed, youth and action; of violence and conflict... a passionate enthusiasm for the beauties of the industrial age" (Rye, 11). It was this adoration for the industrial age that led the painters of the movement to focus on speed and dynamism in their works. Such paintings like Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (Figure 2) and Giacomo Balla's Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (Figure 3) show how these artists were able to depict speed and motion through the medium of painting. Each image looks like a blur as if the painter was capturing the entire range of a motion as opposed to a single moment in time. Even though Futurist painters focused on dynamism to celebrate the industrial age, their visual artistry is actually where Futurism and cinema first cross paths.

During this fruitful time for film, the radical new art called Futurism was started by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. In his manifesto, Marinetti described Futurism as "the exaltation of speed, youth and action; of violence and conflict... a passionate enthusiasm for the beauties of the industrial age" (Rye, 11). It was this adoration for the industrial age that led the painters of the movement to focus on speed and dynamism in their works. Such paintings like Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (Figure 2) and Giacomo Balla's Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (Figure 3) show how these artists were able to depict speed and motion through the medium of painting. Each image looks like a blur as if the painter was capturing the entire range of a motion as opposed to a single moment in time. Even though Futurist painters focused on dynamism to celebrate the industrial age, their visual artistry is actually where Futurism and cinema first cross paths.

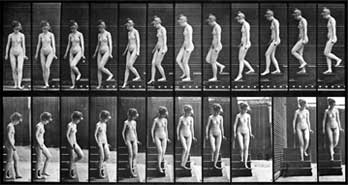

It is no accident that Futurism was born during the cinematic boom, yet Futurism should not be viewed as merely another art movement, but as a reaction to this new form of entertainment itself. The premise of cinema is creating movement through a series of still images, which is impossible in the medium of painting. The Futurists painted what would be the inverse of the cinema: the creation of movement through a single image. If one were to overlap every image of the horse taken in Muybridge's experiment, the result would look strikingly similar to Balla's Dynamism of a Dog, or The Hand of the Violinist (Figure 4). Even paintings like Duchamp's Nude could be viewed as a reference to the origin of cinema, mainly Muybridge's work Woman Walking Down Stairs (Figure 5). Also, for cinema to be experienced, the actual movement of the film through the lens of a projector is required to create a moving image, yet in Futurism paintings absolutely no movement is required to experience the painting's representation of movement. This unique and radical movement showed the world that painting is capable of doing what science had just invented.

In the early 20th century, cinema was no doubt one of the most captivating advancements in technology. And while the early filmmakers and futurists both eagerly embraced new technology, the Futurists had a far different agenda than the early filmmakers. Even though filmmakers where using this brand new technology of cameras and projectors, the stories they were choosing to tell were old fashioned and conservative. Directors like D.W. Griffith and Edwin S. Porter were using the cinema to show morality plays, such as Griffith's "A Drunkard's Reformation" (1909), and stories of the old west, such as Porter's the "Great Train Robbery" (1903). This would have gone completely against the ideals of the Futurists who desired "the complete renewal of human sensibility brought about by the great discoveries of science" (Tisdall, 8). Futurists looked toward the future advancements of man, even to the point of desiring to burn down libraries. The Futurists' paintings showed this foreword-thinking attitude, even if the cinema was still looking to the past for inspiration.

In 1915, D.W. Griffith released The Birth of a Nation (1915), the movie that changed how audience's and critics viewed cinema. It was also that same year that Futurism died in the trenches of World War I. The movement's leaders, Boccioni, Marinetti, and Russolo all enlisted in the army. While this was perfect for a futurist since the basis of Futurism was "to glorify War—the only health giver of the world" (Rye, 7), this led to the movement's demise since both Marinetti and Russolo were severally wounded and Boccioni was killed by falling off a horse (Rye, 153). While Griffith's film was reaching countless audiences, the Futurists' movement dwindled and became overlooked.

Even though Futurism quickly disappeared at the start of the First World War, Futurism should not be remembered as merely another movement amongst the history of art, but as art's reaction to the newly popular medium of cinema. By showing that painting can capture the same dynamism as motion pictures, and still maintain a forward thinking attitude toward future industrial achievements, the movement proved that art was still able to hold a prominent place amongst the new technology that was being developed. And even though a hundred years later, the cinema has not decreased in popularity, Futurism will always be a reminder to artists and art enthusiasts that there are no limitations to art's possibilities.

Works Cited:

- Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner’s Art Through The Ages: The Western Perspective. 13th ed. 2 vols. Australia: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010. Print.

- Rye, Jane. Futurism. Great Britain: Studio Vista, 1972. Print.

- Tisdall, Caroline, and Angelo Bozzolla. Futurism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Print.

2 Comments

By Tiel Lundy on April 14, 2011 at 11:05 AM

This is an excellent informational essay on Futurism. Naturally, the English teacher in me appreciates the graceful prose and strong organization, but I find especially effective the examples of classic paintings and film stills that demonstrate the affinities the two mediums share. (As an aside, Muybridge's "Woman Walking Down Stairs" is a trip, isn't it? It's part of that early 20th-century era in which the artistic, scientific, and prurient intersect. I can't help but think of the work of Thomas Eakins, even though it's part of the Realist school of painting, not the Futurist)

Thanks for the fascinating posting!

By Tiel Lundy on April 14, 2011 at 11:06 AM

P.S. - I like your profile picture. It's both revealing and concealing at the same time.

Leave a Comment